Becoming a Student Again

Adrian Strooberg

TISA

Published:

From Young Gun to Reflection in the Mirror

I was 23 when I walked into my first classroom as a teacher, fresh-faced and ready to inspire. By 25, I had taken the leap into international teaching, with dreams of becoming a John Keating figure from the Dead Poets Society. I imagined my students looking back on their time in my class and remembering me for making their course fun, exciting, and memorable. The truth is, in those early days, I was probably more focused on surviving each lesson than inspiring anyone. I remember riding the staff bus to my school in Dubai, feeling a wave of nerves every time the building came into view. My stomach would churn, and a familiar anxiety would settle over me as we rounded that final corner. In all my lessons, my students were probably watching the clock as much as I was, hoping time would pass quickly. It was a terrible feeling, and I didn’t enjoy teaching those first couple of years.

Fast forward to today. I’m 35, feeling a lot closer to Keating’s age. I don’t feel that dread wash over me on the way to work anymore, but what does that actually mean? Maybe the nerves once pushed me to plan better lessons or think more open about what my students needed—who knows, I can hardly remember. This got me reflecting over the last few weeks. Am I the teacher I set out to be? Maybe, I’m not sure.

Instead of fixating on that question, I decided to step back, look at myself in the mirror, and say, “Hey, you’ve got 30 years le of doing this. How can you inspire better?” How can I leave my students saying, “I love math because I once had this really interesting teacher who made me feel like I mattered,” or “He had a way of teaching me difficult things.”

Oen standing in front of a mirror and asking yourself a question doesn’t give you instant answers.But I did experience one thing recently that I think has put me in the right direction.

I Became a Student Again

Recently, I took on a challenging math course at the suggestion of a colleague. “Go for the hardest one,” he said, and a few weeks in, I regretted it deeply (deeply). But this experience turned out to be precisely what I needed.

Sitting in a lesson, struggling with complex concepts, reminded me just how overwhelming learning can be. I had forgotten what it felt like to be the person who has no idea what’s going on—staring at beautifully craed graphs and equations yet feeling utterly lost. Someone else was explaining them to me from this imaginary golden throne of knowledge, expecting me to follow every step of their example and then attempt an exercise that looked completely different from the one they’d just described. Oh yes, I remembered exactly what it felt like to be in high school math class again (luckily, this time, the teacher didn’t know where I lived, and I could, if I wanted to, disappear). I had taken for granted that linear equations, so clear in my mind, were alien to my students. How could I expect them to grasp concepts I wasn’t guiding them through carefully?

I learnt a lot by becoming the student again and I wanted to share my experience. I’ve outlined four key takeaways from this process, which I’ll go into in more detail below, concluding with why you should also consider how you’re reaching your students. Are you doing everything you can for them? Are you the teacher you set out to be?

- Math is hard

Through this experience, I gained a new perspective. Becoming a student again made me realize that math is hard. Really, hard. It’s confusing, and unlike some other things, it doesn’t come naturally to any of us. We aren’t born mathematicians—we have to work at it, wrestle with it. And I had forgotten how unnatural it can feel to learn something completely new.

Students need to be given time to struggle with new concepts or ideas. They need think time, and they need to be given opportunities to practice what we are teaching them. They need homework, and we need to check that they are able to do it. (Some might have to do it at school, because at home they don’t have the right environment to learn in, therefore we need to know our students).

- Adopting UDL approaches when designing lessons or activities

I also learned that not everyone will understand me, no matter how clearly I think I’m explaining things. Students come with different learning styles, and it’s my responsibility to meet them where they are, not expect them to meet me where I stand.

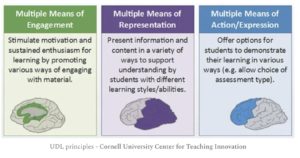

I have to plan for this through Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a teaching approach that accommodates the needs and abilities of all learners and eliminates unnecessary hurdles in the learning process. That means I have to plan carefully, keeping in mind what my lead teacher recently said—a line that really stuck with me: “Who will my teaching not reach today?” I need to think about and accommodate that student too, making sure my approach considers every learner.

- The Hard Reality of Asking for Help

One of the toughest lessons was realizing how hard it is to ask for help. As teachers, we tell our students to ask questions, but we forget how vulnerable it feels to admit you don’t understand. Sitting in class, confused and frustrated, reminded me just how much courage it takes for students to raise their hand. It’s not easy, and I need to be more mindful of creating an environment where they feel comfortable doing so. I need to use multiple strategies to assess where my students are before, during, and aer a lesson. It’s not necessarily more work; I just have to be mindful of it, recognize its importance, and commit to doing it. I also must consider how I react to students who don’t “get” something. Because I’ve planned for that, it’s easier to address misunderstandings during the lesson or set up a time to meet with the student one-on-one or in a small group.

- Small Successes Matter

Another thing I learned is the power of small successes. When you’re a student again, you quickly realize that getting the answer isn’t the whole story. It’s the process of getting there, the little victories along the way, that make learning rewarding. Solving one small part of a problem can build confidence in ways we often overlook as teachers.

This made me reflect: how pften am I helping my students recognise their small successes? How often am I making them feel accomplished, even when they don’t have all the answers yet?

As students enter my class, I ask them to complete a “Do Now” activity. My goal is to get them thinking about math and to warm up their brains for mathematical problem-solving. It also serves as a way for me to gauge their grasp of the concept we’ll be covering that day or see how well they remember something from our last lesson. I aim to help them feel successful right at the start of the lesson; I want all of them to be able to approach the question, at least partially if not fully. This sets the tone—they know they’ll need to think and stay focused, but they also feel confident that they can tackle the work ahead.

Why It Matters for My Students—and For Me

Becoming a student again changed the way I teach. I’ve become more patient, more understanding of the struggles my students face daily. I now see their confusion not as a sign of failure but as an opportunity to support them better. I’ve started focusing more on the journey of learning—how they get there, not just whether they arrive at the right answer.

And the effect on my students? I’ve noticed a shift in the classroom. They’re more willing to ask questions, to admit when they don’t understand something. They’re starting to see that it’s okay to struggle, that learning takes time and persistence. The environment feels less about performing and more about growing together.

Who knows—maybe now I’m finally on track to becoming a little more like John Keating (minus the dramatic desk-jumping, for everyone’s safety).

Why You Should Become a Student Again Too

If you’re a teacher—or even if you’re not—take the plunge and become a student again. Whether it’s math, music, a new language, or something you’ve always been curious about, the experience will change you. It will reconnect you with the vulnerability, the challenges, and the excitement that come with learning.

Sign up for that course, pick up that instrument, or dive into a new subject. You’ll come away not only with new knowledge but with a deeper empathy for your students and a renewed passion for teaching.

P.S. If you haven’t studied math in a while, maybe don’t jump into the most difficult course right away. Ease back into it.

References:

Cornell University Center for Teaching Innovation. (n.d.). *Universal Design for Learning (UDL)*. Cornell University.

https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/universal-design-learning#:~:text=Universal%20design% 20for%20learning%20